April 05, 2008

The doctrine of the farm

Aspiring amateur agrarian, Ben speculates that his engineering friends who dream of becoming farmers may be engaging in "subconscious rebellion against the rampant specialization of modern life."

I think he's right, but for me, it's not subconscious.

An old friend of mine, who worked as a farmer in Maine, once quoted Emerson to me to explain his motivation. He wrote, "When people ask me why I work on a farm, the best answer I can give is that once I read Ralph Waldo Emerson's essay entitled, "Man The Reformer" and I found it to be so compelling, so resonant, that I could not ignore it."

He then quoted from the passage below:

"But the doctrine of the Farm is merely this, that every man ought to stand in primary relations with the work of the world, ought to do it himself, and not to suffer the accident of his having a purse in his pocket, or his having been bred to some dishonorable and injurious craft, to sever him from those duties; and for this reason, that labor is God's education; that he only is a sincere learner, he only can become a master, who learns the secrets of labor, and who by real cunning extorts from nature its sceptre."

While I don't find Emerson's claim compelling enough to move to the sticks and plant an apple orchard, I do feel compelled to resist the specialization of labor, to the extent that I know how. As my friend Alex once pointed out, none of us are pure-- "What are you going to do, smelt your own metal?" All the same, I try to reduce the distance between me and the work done on my behalf in the world.

It's a curious bind. As an engineer, I'm at the extreme end of specialization, but I'd much rather spend the afternoon repairing a friend's bureau than working for higher wages that I might pay to a carpenter to repair the bureau.

I had a friend's mill in my garage for a while a few years ago. I didn't use it very much, but I spent a fair bit of time doing maintenance on it-- rewiring the switchbox to make it a bit neater, replacing some of the crappier fasteners with stainless socket head cap screws, and so forth. I'll be the first to admit that that sort of behavior is pathological.

Still, taking care of the mill gave me a satisfaction that I've found hard to duplicate, despite my work as an engineer. Typically, the manufacture of stuff I design, and hence the care of tools, is performed by machinists, who will work for a lower wage than I do.

I suspect that a good deal of my desire to inject myself into the workings of machines is genetic. My dad, for example, mentioned to me a while back that in the 70's he wrote a FFT subroutine in machine code (not assembly-- he was typing raw hex). It makes me polishing the old mill look rational.

When I was a kid, I remember my grandfather finding a toy van in the garbage on the way to the beach. He replaced the floor in the van and repainted it, and my brother and I got to play with it whenever we came to visit. At the time, I was delighted. Looking back now, doing automotive maintenance on a vehicle too small to drive seems odd.

Regarding specialization, Wendell Berry wrote in 1977 in The Unsettling of America:

The disease of the modern character is specialization. Looked at from the standpoint of the social system, the aim of specialization may seem desirable enough. The aim is to see that the responsibilities of government, law, medicine, engineering, agriculture, education, etc., are given into the hands of the most skilled, best prepared people. . . . The first, and best known, hazard of the specialist system is that it produces specialists - people who are elaborately and expensively trained to do one thing. We get into absurdity very quickly here. There are, for instance, educators who have nothing to teach, communicators who have nothing to say, medical doctors skilled at expensive cures for diseases that they have no skill, and no interest, in preventing. More common, and more damaging, are the inventors, manufacturers, and salesmen of devices who have no concern for the possible effects of those devices. Specialization is thus seen to be a way of institutionalizing, justifying, and paying highly for a calamitous disintegration and scattering-out of the various functions of character: workmanship, care, conscience, responsibility.

The disintegration of workmanship, care, conscience, and responsibility is what drives me to resist the deepening of specialization. I want to avoid the conclusion that stuff should be left to "the experts." No need to fix your toilet, a plumber will do that. No need to drag your trash to the curb, the condo manager's henchman will do that. No need roust your corpulent form from its slumber, your mechanized exoskeleton will do that.

This next paragraph is a bit of tangent, but it's a good story and a metaphor as well. My experience has been that you can achieve more than you might expect through severe effort. Around 1998, Oliver, Alex, and I were trying to move a very heavy, slate-topped lab bench from a quonset hut across some dirt and weeds into a workshop. We tried moving the table, and only managed to move it a few inches on the first attempt. Oliver and I started talking about going to get a furniture cart, or a dolly, or maybe a sled of some sort. Alex broke in and said, something like, "We're not getting a cart. Just push harder. Come on. Push." This effort was successful and taught me a good lesson about the use of force.

I've found repeatedly that my overly-specialized contemporaries generally assume that anything more difficult than lifting a coffee pot should be left to professionals. A few weeks ago, I was helping my parents clean some junk out their basement when we came across the trestle built from 1x3's from an old worktable that would make good fodder for our woodstove. My mom made a comment about needing some tools to disassemble the trestle. I was able to wrench it apart in less than 30 seconds.

Sometimes I feel like I've discovered a lost secret. "No, really, you can sharpen knives by hand with a stone." "No, really, you can make your own Ethernet cable that's as long as you want. You just crimp the wires like this."

The feeling of doing good work yourself is surprisingly liberating, and a little sample breeds a taste for more. After a little while, you're in danger of attempting to reject industrial society entirely. As Wendell Berry writes at the conclusion of his 1993 essay, The Joy of Sales Resistance, "When the inevitable saleswoman comes to tell me that I cannot be up-to-date, or intelligent, or creative, or handsome, or young, or eligible for the sexual favors of so fair a creature as herself unless I buy these products, dear reader, I am not going to do it."

Oh, also: I paid $4.20 for a gallon of diesel this week.

March 18, 2008

From teaching high school to renewable energy engineering in less than 10 years

"Ultimately, my goal is to work at a small engineering company developing alternative transportation technology-- projects like the solar car, but more practical."

That was the first sentence of the second paragraph my graduate school application essay, submitted July 27, 1999.

7 years and 1 month later (August 27, 2006), I started working at GreenMountain Engineering. It took another 5 months before I was actually working on an alternative transportation project (a battery pack for a hybrid bus). I developed the goal a year or two before applying to graduate school. In total, it was a few months less than 10 years ago that I decided I wanted to do more or less what I'm doing now.

Maybe engineering is easier than programming.

Ten years from now? I hope that some of my efforts will have been successful. I hope it won't be normal for my fellow Americans to drive cars with an average fuel economy of less than 30 miles per gallon, and I hope that some of our 140 servants will have been replaced with renewable sources of energy.

A more modest hope, given the hullabaloo on Wall Street this week, is that I'm not compelled to load up on handtools and firearms and head to the tropics before the Hard Times arrive.

Gotta focus on "losing the apocalyptic mindset," in the words of a friend . . .

February 24, 2008

Popularizing the backyard zoopraxiscope

Hard times evangelist Ben Polito asked an interesting question on his blog a week ago: "Why is it that even people who care about [global warming and oil supply issues] don’t actually make relatively simple choices that could significantly reduce their impact?"

I've wondered about this myself. Our behavior is complex, but I think the answer is that we are accustomed to the idea that environmental problems can be solved by marginal changes. There are two ideas here-- that our behavior is guided by our expectations of what sorts of behavior are customary, and that marginal changes can solve big problems.

Our yard is an example of the first idea. We live near the corner of two streets with a decent amount of pedestrian traffic and near a convenience store. The result is that trash is thrown in our yard at a rate of a few liters per month. There are two trashcans near the convenience store (and I don't really know that the trash comes from the patrons of the convenience store), but people definitely throw trash over the fence into the bushes in our yard on a daily basis.

Mysteriously, of the thousands of hours I have spent walking around neighborhoods with other people, I have never-- seriously, never-- seen one of my friends throw trash in anyone's yard, and I have never done so myself. I suspect that I live in a culture where littering is unacceptable, but I live in a city where a decent fraction of the population lives in a culture where littering is normal. It's not that I think about throwing trash on the street every day but decide not to-- I don't even think of it.

To bring it back to climate change: I suspect that most people, even those who care about climate change, don't think carefully about their levels of energy consumption. They feel worried about sea levels rising and hot summers, but knowing no solar hermits or people who grow most of their own food, they don't place those among the options. To the question, "Want to see a movie tonight?" they do not answer, "Yes, let's build a gigantic zoopraxiscope in the backyard." Instead, it's "Hmm, we already saw An Inconvenient Truth. How about the new Rambo movie? I know Sylvester Stallone is 61, but I hear he does all the killing with his shirt on." Options that don't involve living in a house regulated to 20 °C year-round and driving a car on a daily basis are not on the menu.

The second idea is the strangely common conviction that we can solve large environmental problems with marginal changes to our current behavior. I don't know why this idea so popular. Suppose Ben invited me over for dinner party, and heavy rains meant that his basement was flooded. If I suggested to the dozen other guests, "Hey guys, I've got a great idea. We'll each take one of these drinking glasses down to the basement and fill it up. We'll bring them back up and pour the water on Ben's vegetable garden. If we each do our part, we all win!" I would be correctly regarded as a moron. The problem requires a high capacity pump running for several hours, or hundreds of trips with a bucket, or thousands of trips with drinking glasses.

Our bizarre love affair with hybrid cars is similar. Let's optimistically assume that hybrid cars can reduce fuel usage per mile by 50%. The real number is probably below 25%, but say the technology works better than we expect, and then assume that every vehicle in the US is instantaneously converted to use a hybrid drivetrain. In the US, at present, our fuel consumption for transportation usage has been growing roughly linearly for the last 60 years [58 kB PDF]. The best we can expect for this massively optimistic, nationwide hybrid conversion is to return ourselves to 1970, but with 40 years of oil gone.

Ben asks what we can do. As he notes, "There’s also a sense in which it is irrational for any one person to make any significant sacrifice in order to change his behavior, on a planet with 6 billion people, the vast majority of them striving to achieve a lifestyle that allows them to consume as much energy and resources as possible."

In the film metaphor, we need to popularize the backyard zoopraxiscope. Our cultural norms have a time constant around a decade; ideas come and go, and we need to make sure that "Let's all commute 30 miles in SUVs" is not the only movie to watch.

To his credit, Ben, with his wind turbine and cidermaking, has already begun.

I've been commuting by bike exclusively for the last 6 months, even in the snow and ice, and once I adjusted my expectations, it's fine. We've reduced our heating bill by about 30% by using a programmable thermostat; we'll see what else I can come up with. Our current house is about as well insulated as a milk crate, so there is hope.

January 24, 2008

The SL1 is out the door

We finally released our first product at GreenMountain Engineering. I've been working for various different consulting firms (MindTribe, Ideo, and now GreenMountain) over the past few years, and this is the first time I've been involved in shipping a product that wasn't owned by someone else. I feel proud, and I didn't even do the hard part-- most of the development and testing took place in our San Francisco office.

The product is the called the Trac-stat SL1. It's a ridiculously accurate sensor for measuring how closely your solar tracker is aimed at the sun. I think the spec is 0.02 degrees for the more accurate of the two sensors it contains.

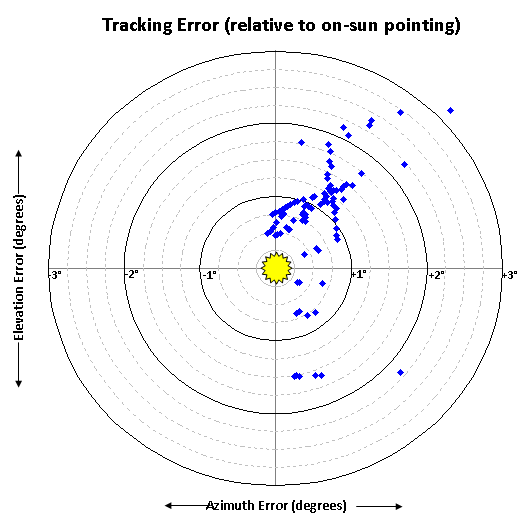

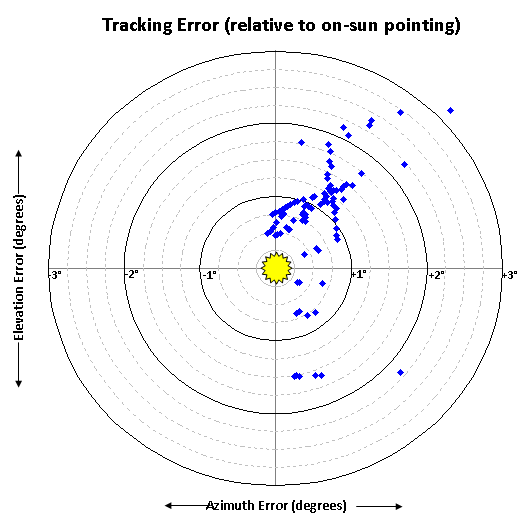

Max and two of his west coast disciples have been testing it at our secret rooftop testing facility in San Francisco for the last few months. (Pretend you don't recognize the lights of the Giants' baseball stadium in the background.) The graph below shows the output of the sensor. This was on a tracker of relatively low precision that we have used for a couple of different concentrating solar projects.

Of the many markets that exist for the SL1, the largest is the group of companies that are trying to build concentrating photovoltaic systems. The key point of leverage behind concentrating solar is that if you can gather the same amount of sun with a drastically reduced amount of solar cell, you can win on cost. An unfortunate side effect is that as your target gets smaller, you need to aim ever more precisely at the sun. This means that to be able to evaluate the performance of your concentrating system, you have to know how well you are pointed at the sun. This alone is a serious research project; there is substantial empirical evidence that building a sensor to track the sun takes lots of work, and that doesn't even get you any actuation. You can buy a pretty good tracker, but you won't know how good unless you have some sort of diagnostic instrument that can measure your error very precisely.

When I worked in the Stanford Robotics Lab after grad school, a shrewd man told me on one occasion, "Don't make everything a research project." (I think I was proposing writing my own TCP/IP stack or something similarly idiotic that would have taken long enough to preclude completion.) My hope is that the concentrating solar companies will not spend the engineering time it would take them to each build an SL1 equivalent.

And finally, did I mention that it also has a sweet command line interface?

(Perhaps I should note that the opinions listed above do not represent those of my employer. Especially not the unreasoning zeal for command line interfaces.)

older postsnewer posts